Sacralized Space:

Theaster Gates on the Practice of Placemaking

Moderated by Alice Grandoit-Šutka & Nu Goteh

Photography by Nolis Anderson

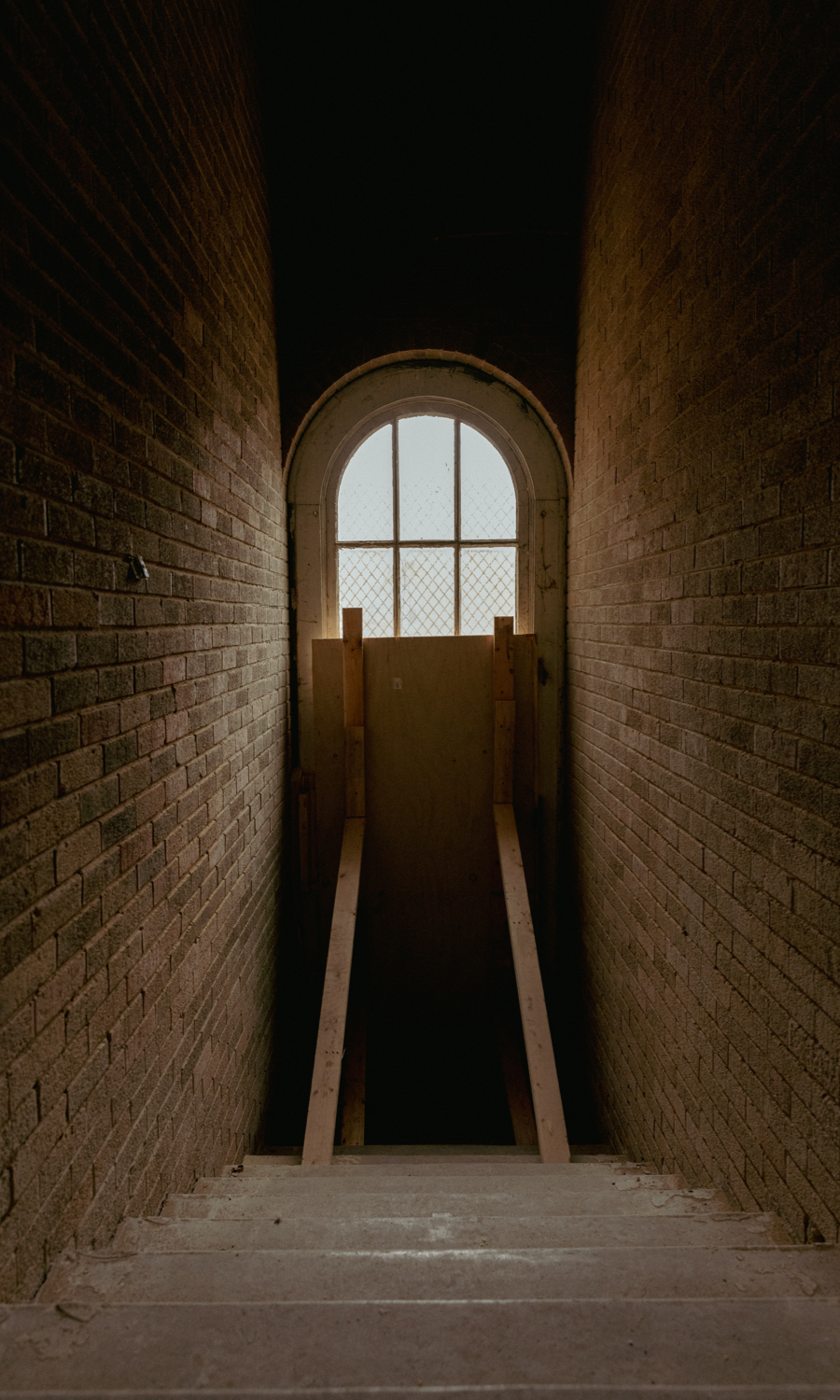

A portrait of Theaster Gates. The photographs that accompany this story were taken by Nolis Anderson at the St. Laurence Elementary School on Chicago’s South Side.

ALICE GRANDOIT-ŠUTKA: Our fourth issue of Deem is centered around the theme and concept of place. What does place mean to you? How do you consider space differently from place?

THEASTER GATES: Place. It’s the ability to locate oneself where one belongs. Place is the manifestation of care. With location alone, you’ve got space. With location and familiarity, intention and love, you’ve got place. I think that the work that I’m involved in is constantly trying to bring intention, beauty, and love back to location.

AGS: How might one sense the differentiation between the two?

TG: When I was studying at the University of Cape Town, I worked with a gentleman named David Chidester. He taught a kind of psychology of space, as well as theories on religious space. We were thinking about traditional African religious space in particular. The question was, within a community, how do you sacralize a space or, in other words, how do you convert it from a space to a place? His theory revolved around a leader. The person says that they believe the space in question is sacred or could become sacred in the future. Then, a community of people gather around that person and say, “We believe with you that the space that you’ve identified could become sacred.” The first thing they do is clean the space. Then they designate the space by drawing a circle or forming some kind of edge, so that sacred things can happen inside the perimeter, and non-sacred things can happen adjacent to and outside of the perimeter. Once this process is complete, they begin to do sacred work. They sing, they dance, they move, they make sounds, they express themselves in the space, and then they wait for something sacred to happen. They wait on God to show up. They wait on the spirits to descend. But they action, they labor, until God becomes present.

I think when I came back to the South Side of Chicago, I was entering a place that I could tell had been sacred but was no longer deemed as such. Then I said, “I believe that this space could be sacred,” and the people around me agreed, “We believe with you.” Then I started cleaning. Then we stepped into the perimeter and started laboring. And when God showed up, it seemed like others showed up, then institutions showed up, then resources showed up. And when those institutions and resources showed up, those things also conferred that the space had become sacred.

“The crux of my work is a hunger and thirst for meaning and the capacity to make meaning.”

NU GOTEH: You’ve been described as a “social practice installation artist,” meaning that you work directly with people and communities rather than only depicting, imaging, or speaking about them. This is quite unconventional within the art world and industry that you are also a part of and, unlike the tradition of “relational aesthetics”—which contained these interactions within art world contexts and places—the social networks you work within are based in the real world. Why is it so important that social practice be the crux of your work? Did any particular experiences or inspirations push you in this direction?

TG: The crux of my work is a hunger and thirst for meaning and the capacity to make meaning. And that capacity to make meaning splits itself, if you will—splits itself between things that happen in the studio and things that happen outside of the studio. I had never imagined myself as an artist of or within relational aesthetics, but I know that Black people are relational. I’ve got a good relationship with my family. I got homies and, in a way, I have a sufferable disease that deals with the desire to be connected, to be loved, and to love. And so, rather than bifurcate my life between object-making and seemingly more social activities, I ball it all up together. In some ways, it’s the success of my object-based practice that has allowed my sociability to become so evident in the world. That is, I would not have a bank if it was not for my Tar Paintings. I would not have a cafe if it wasn’t for my Civil Tapestries. There would be less free, cultural activity if I wasn’t deeply engaged in the creation of beauty through objects. Let’s say that.

First and foremost, I feel like an artist who makes things. Then, I feel like an artist who believes in people. What’s interesting about this moment—or this last decade—is that art history has started to exhume the social aspects of artists from their actual practices. I think artists have always been engaged in social practices and relational aesthetics. There was just no name for it. But just because there was no name or taxonomy doesn’t mean this didn’t exist. I think art history has done a trick, so that now we seem to believe that just by being social, we’re being artful, which is reasonable, I suppose.

I feel like Black artists especially have the burden of “cousins,” and I’ve had this conversation with other artists of color. Would we be greater if we were selfish? Would we be ostracized for our autonomous influence if we weren’t spreading the love? Or is the guilt more an internal conundrum where the Black artist feels that he or she must bring along the entire South Side of the city of Chicago on their boots, on their coattails—that there is no me without we?

The truth is I’ve benefited greatly from the social aspects of my work. The Stony Island Arts Bank is the love of my life. The activity that happens in the Arts Bank, the Retreat at Currency Exchange Café, and the Black Artists Retreat—these moments—they’ve defined who I am, in a way. And I’m talking about what I do in a day. I feel fortunate that I get to wake up in the morning with a love for object-making and a love for people, while also having strategies and platforms whereby those things play out. But when I try to remember where I started, it had something to do with the desire for meaningfulness. And that meaningfulness needed pathways.

“Theories around being together are already acknowledging a kind of dysfunction in the social order. But does one need theories around how to be with each other?”

AGS: According to architectural theories that arose in the 1960s, “placemaking” involves intentional building and design practices that enculturate community by using space to connect people through the experience of sharing it. You are involved in a variety of public projects that engage such priorities, such as the Dorchester Projects and, the aforementioned love of your life, the Stony Island Arts Bank. We’d love to take the Rebuild Foundation, your community development model, as a starting point. What are some strategies that you apply in this kind of work? What have you learned in this process?

TG: Alice, what’s so great about this conversation is that I haven’t really had to take a whole lot of time to think about how to build community. Theories around being together are already acknowledging a kind of dysfunction in the social order. But does one need theories around how to be with each other? There’s a part of me that feels like some of these things, as profound as they might seem, are actually an extension of our nature, and I feel strange about giving strategy to something extremely natural.

Let’s talk about Dorchester. I was broke. I was not professionally engaged in the contemporary art community, so I would host events at my house. My events are probably one iota of fun in comparison to the rent parties my brothers-in-law and my sisters hosted in the ’80s. A rent party was the equivalent of the Taste of Chicago. A block party was like Mardi Gras. When you think about Black sociability—whether it’s the mosque, the church, the club, the 4th of July picnic, or the family reunion—Black people know how to get together. The challenge is that we don’t always own the space. We don’t always own the location of our conviviality. The only thing that I flipped was the incessant need to own the ground beneath us, because it allowed for other kinds of rights. It gave me a certain protection.

Listening House and Archive House. Photograph by Sarah Pooley.

I remember, there was an empty lot to the south of my house on Dorchester. I invited a young artist, Devon Mays, to host an event. They erected some teepees, and there was music and a healing activity happening on a lot that was owned by the city. The police came by and they tried to shut me down. I said, “Officer, this is the best thing that’s happened on Dorchester in the last 35 years. We are actively keeping bullshit away. The kids are having a great time. They’ve never seen a teepee before. Please do not shut this down.” The officer said, “Sir, do you own this parcel of land?” It was that day that I was like, “Oh, let me buy that. Let me buy that lot.”

So I bought that lot. I bought that lot because I didn’t want a cop telling me what the fuck I could and couldn’t do on my block. Then I bought another lot. Then I bought the house next door and every indication of negative deviance happening in my space. I bought that house and made it a place. What is placemaking? It is the continual renewal of desacralized Black space into newly sacralized Black space through love and attention and community. Am I a placemaker? I don’t need no theories. I like kicking it with people. I like being in love. I like to be loved in my community. I want the people around me to feel like we built a garden together, and that it’s as much theirs as it is mine. And I’m also talking about leadership, the impetus of the thing, who gets the party started. I’m the first one on the dance floor. Placemaking is about being willing to be the first one on the dance floor until the whole floor is full.

AGS: Well, I think both Nu and I can relate to this framework, as well as to the types of knowledge one generates within the context of a party or a celebration. That’s a big part of how we came together in our early twenties and is a metaphor that we try to bring into our design practices as well.

NG: Let’s talk about archiving. Your work also involves the possession and stewardship of several archives that are housed in the Arts Bank, including books that once belonged to Ebony and Jet founder John H. Johnson, and legendary House DJ Frankie Knuckles’s record collection. A part of this issue will also focus on examining how place is created and preserved outside present time. How do you want your archives to function and what do you hope that they can convey?

First image: Stony Island Arts Bank. Photograph by Tom Harris. Copyright Hedrich Blessing. Second image: The Johnson Publishing Library at the Stony Island Arts Bank. Courtesy of Rebuild Foundation. Third image: Frankie Knuckles Vinyl Collection at the Stony Island Arts Bank. Courtesy of Rebuild Foundation.

TG: Most of my things are Black things. I collect these things because I am, again, trying to demonstrate that Black things are important, and that if one practices caring for things, one practices nation-building. If we could build nations, then we could also actively resist and remember the collateral damage that has happened to us over generations. We could remember our whole selves. If we don’t retain the objects of our past, if we don’t develop a muscle for caring, we’ll find ourselves left with the things we’re constantly being encouraged to buy. The only semblances we’ll have of ourselves will be the semblances that others have made for us.

What an album represents, especially when it’s an album that belonged to Frankie Knuckles or Jesse Owens, is evidence that there was a Black person present at the inception of a musical movement—in this case, among the progenitors of House. A collection of objects gives us a material glimpse at someone’s brain, and offers us a corpus of their life’s activity. It drives me wild to be a curious ally to the past, and to use these objects to create base knowledge for the future intelligences of people, Black and otherwise. The archive at the Arts Bank also creates a reason, a seductive reason, for people to gather. The only way one can experience the archive is by visiting in person, and coming there brings new energy to and resacralizes the space.

First image: vinyl from the Frankie Knuckles Vinyl Collection at the Stony Island Arts Bank. Second image: a single glass lantern slide from the collection of over 60,000 University of Chicago glass lantern slides at Rebuild Foundation’s Stony Island Arts Bank. Third image: books from the Johnson Publishing Company Library, one of Rebuild Foundation’s four permanent archives at the Stony Island Arts Bank. Fourth image: books from the Ed J. Williams Collection of “Negrobilia” housed at the Stony Island Arts Bank. All images courtesy of Rebuild Foundation.

AGS: You are also a trained ceramicist, and much of your early work addresses Japanese ceramic tradition and its intersection with ceramics in Black American culture. You even invented a character—potter and Mississippi resident Shoji Yamaguchi—as a parafictional way to express this synchronicity. Could you tell us more about how Japan has influenced your work, and perhaps also your imagination around place?

TG: All my life I’ve looked for markers of excellence and I’ve found them everywhere. I visited Japan and was immediately humbled and moved by the intelligence of hand I saw all around me.

I remember one day going to the ceramic workshop where I studied to make what I thought to be a beautiful Japanese tea bowl. The teacher came over to me and said, “What are you doing?" I was like, “I’m making a Japanese tea bowl.” And he was like, “Why are you doing that?” And I said, “Because I’m in Japan.” Then he was like, “But there are great potters in Mississippi.” He was talking about a guy named William (Wild Bill) Ohr. They called him the Mad Potter of Biloxi. He asked me, “Why are you not making Mississippi pots? Why don’t you make a Mississippi bowl?” And I was like, I’ll be damned! I had to go all the way to Japan to be told I should be making the pots of my people. That’s when you know that it’s philosophical. It’s bigger than the object. For the rest of that trip and long after, I thought to myself, “What kind of bowl do I need for the foods of Black people?” It totally changed my sensibility. I started making a plate with a lip because I needed to get up against something. I can’t eat no collard greens on a flat plate—where’s the juice going to go?

The idea of Yamaguchi was a way of reconciling a new binary, which is a life ungoverned by the preoccupation with whiteness. In fact, I’m preoccupied with excellence. This framework was another way of working out my Blackness through othering, and specifically self-othering. How do I know myself to be myself?

NG: You have spoken extensively about your ideas around the expanded role of the artist within society, while also making it clear that artists should not be burdened with the responsibility of alleviating injustices in their communities. One thing that affects the artist-community relationship is many artists’ perceived need to move away from where they are from in order to have a successful career or make money from their work. What is the importance of artists’ relationship to the place they are in and/or from? Our Issue Two cover story with Lauren Halsey, for example, offered a great blueprint for an incredibly fertile and symbiotic artist-community relationship. What would need to change in order for more artists to feel able to “stay home”?

TG: I love Lauren, and I’d like to make this a little bit of a personal story. There’s a generation between Lauren and I, artistically. And then there’s a generation between me and, say, Rick Lowe, in terms of artists who stayed in a place and tried to do a thing that was about a place. What we share is a strand of ideology or philosophy that says it’s okay to be where you’re from and work out of that place as the principal fodder for one’s artistic imagination.

I think that, because of individuals like Rick, Gordan Matta-Clark, Donald Judd, Martha Graham, Alain Locke, Mark Bradford, James Turrell, and Gertrude Stein, there have been people over time who understood the power of place. And by anchoring deep down in a place that they’re from, or that they choose, they were able to build a world around them. I believe that sensibility is just in some people, and I think I have an artistic practice that is rooted in staying—the politics of staying, you might say. I don’t think it’s the burden of the artist to have to stay anywhere, but the artist has the ability to choose place as a strategy among other tools in their toolkit. And, by choosing place as a kind of artistic imperative, make things happen through it. If there is anything I could offer young artists, I would say, be boldly where you want to be and really, really be there. I feel very fortunate that I was able to work through the trauma of home to be a stronger self.

NG: To close, I’m going off script. Theaster, during our photoshoot earlier this week, I asked you about your choice to be barefoot. Your response, which has stuck with me, was, “I’m country as fuck.” We shared a laugh, but the conversation evolved to encapsulate what we each need, as a human, as a Black person, as an artist, to be boldly in our place. Prior to this call, I was telling Alice about that exchange and how often I observe that, when occupying predominantly white spaces, we feel a need to assimilate. Even for safety reasons, we feel we have to fit in. But the conversation that you and I were having was more around imagining, “What starts to happen when I control the space, and the place, and what do I need in order to be boldly there?” Is there anything you would add about how we do that—how we create those opportunities to be boldly ourselves?

TG: Two things come to mind. The first is the work that actors and performers do to practice centering, so that they can deliver the best version of their craft. This is the ability to shut out the world and find the place within yourself that the good thing comes out of. Everyone needs strategies to counter the noise so that we can get in touch with our sense of self. Being barefoot allows me to access a different part of my brain and, on that day, I knew I especially needed that. I knew I wanted to deliver something very special from my heart, so I wanted to literally feel the ground of this space.

In that moment and that place, I was flowing. The other part has to do with courage—the courage to be oneself. I don’t know if that’s advice, but it’s an admonishment. I think the more one practices being oneself, the more one traverses different states and discovers different aspects of being. Lately, when I’m in a room full of amazing people, I want to be the lo-fi dude, and that’s after years of feeling like I had to be the hi-fi dude. Courage allows you to continue to ask yourself, who am I today? Who do I need to be for myself today? Who do I need to be to others today? More and more, who and how I want to be, wherever I am, is safe, prayerful, reflective, listening.

“If there is anything I could offer young artists, I would say, be boldly where you want to be and really, really be there.”

Theaster Gates is a multidisciplinary artist and social innovator who creates work that focuses on space theory and land development, sculpture and performance. Drawing on his interest and training in urban planning and preservation, Gates redeems spaces that have been left behind. Known for his recirculation of art-world capital, he creates work that focuses on the possibility of the “life within things.” In all aspects of his work, Gates contends with the notion of Black space as a formal exercise—one defined by collective desire, artistic agency, and the tactics of a pragmatist.