Reverence over Reference

Ramsay Taum speaks with Isabel Flower about the Meaning of Place-Based Values

Illustrations by Cory Kamehanaokalā Holt Taum

Ka ipu ka honua, 2022

This first image is inspired from an old Hawaiian chant for the god Lono, comparing the earth to a hanging gourd, and the gourd’s cover to the starry sky. This gourd then hangs from a rainbow as the ‘Auamo (burden pole). This is my humble attempt to translate our ancestors’ visual poetry, which reflects Uncle Ramsay’s mana’o on the Hawaiian understanding of our place in the cosmos.

“The gourd is this great world; its cover the heavens of Kuakini. Thrust it into the netting! Attach to it the rainbow for a handle!”—all captions authored by the artist, Cory Kamehanaokalā Holt Taum

Isabel Flower

This issue of Deem is centered around the concept of place. I want to start by asking what place means to you personally and, if it’s relevant to your answer, what differentiates place from space?

Ramsay Taum

Thank you, Isabel, that’s a wonderful question and reflects a priority that favors relationships rather than transactions. A “place” is where one has a relationship with “space” and the people and things in it. There are places where you experience something specific to you—such as an external connection to your internal space. I like to call it an inside job. What and where is that place that allows you to engage whatever you want or need at that moment? Your residence, for instance, is a place you may look to for sanctuary. In that place there are spaces where you experience and engage in activities that enhance the sense of safety, calm, quiet.

I think place and space go hand in hand, but space is more like a container, a holding environment, while place provides context and content. Depending on what experience I’m looking for, there are different spaces that I seek out and, within those spaces, there are places I’m attracted to. That’s one way of looking at it. With that said, I also think the ultimate space is the internal one. The space between my head and my heart. That space that allows me to think, feel, and connect the two. If you’re not in a place that allows you to become centered, that allows that connection, then that’s not a very good place for you. That internal alignment is what allows me to be present and to fully engage with the people I’m with or the activity I’m trying to experience. There are places that have and create that space.

IF

That was beautifully articulated. It’s been interesting to hear different people’s take on this because there’s been a lot of interpretation. This morning, I spoke to an artist who feels that place is wherever she has a memory. I feel like there’s a relationship between your two perspectives.

RT

Thank you. I think if I were to simplify it further, I would probably end up at the same place. It is all about memory. Certain places and spaces trigger us, and fundamentally, that’s what everything is—memories we are recalling or creating.

I guess place is made when our sense of meaning is activated.

RT

Absolutely.

IF

I’d like to talk a bit about Hawai‘i. As an archipelago, I think there is a special kind of relationship to place because there is a natural isolation. Rather than a politically or culturally constructed sense of a border, there’s a real physical barrier between this place and other land. How do you think Hawai‘i’s geographic physicality affects the kind of place it is, and the relationship of the people who live there to it?

RT

This is another great question, and I’m not sure we have enough time to answer it completely. Hawai‘i is a series of mountain tops we perceive and experience as islands. It is quite literally placed in the middle of the ocean, and what we see on the surface is just a small part. The islands themselves reach deep into the sea. Consequently, we live on mountain tops, which is not so different from the human condition. We tend only to see what’s above the ocean’s surface, yet, like Hawai‘i, there is so much of us that lies beneath the water.

Since we live “in” the ocean, we have a special relationship with it. What we do to it, we end up doing to ourselves. There’s no getting away from it. We are in it. You become very mindful of that relationship. In the middle of the sea, while we may be under the influence of the external environment, we are equally in sync with the internal space as well. Hawai‘i is considered the most remote inhabited place on the planet. You don’t get here by accident. It takes intent. You also don’t leave here by accident, either. That, too, is intentional. If you plan to come and stay here, there are challenges you must acknowledge and navigate.

Kapolioka‘ehukai, 2022This image is dedicated to the many stories about renowned Hawaiian wahine surfers throughout time, from the days of old to modern legends. I hoped to illustrate this sport of the chiefs, and daily ritual of our ancestors, that has since become popular around the world.

RT

Another way to explain what Hawai‘i means to us is to look carefully at its name. It is our home, it is our mainland, it is our main place. The name itself reveals its identity and our relationship to it. For instance, we can break it into three words: ha-wai-i. How you say the name activates it.

The first word—ha—refers to life-giving breath, air. It is the first thing you receive when you come to the planet, and the last thing you give back. Something you always share and can never own. Giving and receiving is foundational to the principle of aloha, which is Hawai‘i. It’s a reciprocity agreement, it’s a relationship with others as well as with this place. It’s breathing in and breathing out. Ha is also the space, the atmosphere between you and I. It’s the air that connects us. Isn’t it funny how, anytime we damage that space, we use expressions like, “let’s clear the air between us,” because we recognize the importance of that space.

The second word—wai—refers to fresh water. Life in this archipelago, or anywhere on this planet, doesn’t succeed without water. We are also surrounded by saltwater called kai. While wai is fresh, kai is salt. This reflects the dualities of life—soft and hard, in and out, up and down, external and internal. A balanced ecosystem requires living in alignment with your surroundings, because if you don’t, you can’t live here; the island won’t allow you to because you won’t have the necessary resources to do so.

The last word is i (ee). The i references the creative forces that some would call God: the divine thought process, inspiration, the spirit that comes from within us, the big “I.” Ha-wai-i, the place of air, water, and spirit—that’s where we are. That is our connection to our place.

“We say we need to save the earth. The earth is fine. The earth isn’t going anywhere, but we might be. What we really mean is that we need to take better care of the earth if we want to survive.”

IF

That’s probably a profoundly different way of thinking from the average person whose mainland is the United States. We tend to think of ourselves as being separate from nature and needing to return to it—this is an idea poignantly expressed by Mia Birdsong in our last issue—instead of acknowledging that we were never not part of it, even when we might feel otherwise.

RT

That’s exactly what I mean when I say we are in the ocean. Yet we say we need to save the earth. The earth is fine. The earth isn’t going anywhere, but we might be. What we really mean is that we need to take better care of the earth if we want to survive.

IF

When I was preparing for this interview, I discovered your work described as “sustainability, cultural and place-based values.” What are some of the place-based values that you center around?

RT

The reason it’s phrased as cultural and place-based values is because I believe it should be “and” rather than “or.” I’m suggesting those are the values we give priority to in the places we are, and culture is the reflection of that relationship.

Take the expression, “You are what you eat,” for example. I can assure you that my relationship with my food is important, as you’ll find is true for most Indigenous people. Some of us even refer to primary food sources as a relative of sorts. My Native American cousins might say, “my brother the bear” or “my brother the deer.” For us, it’s taro. Hāloa is our elder brother and we know that when we “care for our brother, he will care for us for life.” Caring for the land, caring for the air, caring for the water, caring for your food, caring for who you feed—this is what keeps us together as community. This is what makes us "we." If I’m getting my food delivered, then I might only be thinking about sustaining the delivery system, rather than the source of the food itself. What you perceive as directly connected to you changes your behavior. You begin to act differently.

Hawai‘i is no different than anywhere else, but our priorities are. The shift comes when place is based in reverence, not reference. When we order food from across the ocean because we built condominiums on the land that used to feed us, we have changed our priorities. It’s easy to see what our priorities are—just look at how we treat the land and sea. Place-based values come alive when we give priority to the relationship between our resources and one another. Someone who is living in the city versus someone who is living in the desert has a different priority regarding water, right? They both value water, of course. But the person who travels miles to get it and who is aware of its scarcity I think values it a little more than the person who can go to the tap and turn it on. That’s what place-based values are: What do you eat? Where does that come from? Where are you born? Where do you sleep? Where do you die? Where are you buried?

Kameha‘ikana, 2022

Kameha‘ikana is one of the names for the wondrous (literal translation of the word kāmeha‘i) goddess, Haumea. On the Ko‘olau side of O‘ahu, one of her body forms is as a Mo‘o Wahine (Lizard Woman), as well as in the plant form of the Ulu (breadfruit) tree.

IF

Part of what inspired us to choose this theme was noticing that most of our conversations about design occur through virtual interactions and I think there is often a disconnection or disassociation from physical place. We may not even know where the people we’re speaking to are at the time of our conversation. That is the nature of modern life and the ability to move around so easily in a globalized world.

RT

In Hawaiian, we have a way of referring to ourselves before we give our name. If you asked one of my elders—my kūpuna—who they were, they wouldn’t say their name. What they’d say is, “I am Hawai‘i. I am the son of my father and of my mother, who are the sons and daughters of...” Our genealogies connect us to place. I belong to my place, which is also a family, a culture, and an identity. Like you said, today’s world is, in many ways, placeless. Or our sense of place has been relocated to the virtual space of computers, which allow us to be in many places at once. But life always comes back to a few questions, like, who are you? And often that relates to, where are you, and why are you there? What do you value? What do you prioritize? Many of our conflicts in life are not so much about values as they are about priorities.

“Place-based values come alive when we give priority to the relationship between our resources and one another. Someone who is living in the city versus someone who is living in the desert has a different priority regarding water, right? They both value water, of course. But the person who travels miles to get it and who is aware of its scarcity I think values it a little more than the person who can go to the tap and turn it on. That’s what place-based values are: What do you eat? Where does that come from? Where are you born? Where do you sleep? Where do you die? Where are you buried?”

IF

You’ve anticipated my next question, which is around how our late capitalist and globalized world divorces us from place so dramatically that the kind of work you do is both lacking and essential. Historically, this divorce goes back much further than just capitalism and globalization—it is also a product of imperialism and colonialism. What are some strategies you employ in your work to address this?

RT

Something important about Hawai‘i is that we’re still in a natural space that is, for the most part, dictated by natural time. Yet the average person’s experiences of work are dictated by artificial spaces and artificial time. I try to help us recognize how we try to find authenticity in an inauthentic space. Why do I bring a potted plant into my apartment when I could easily step outside? Because my priority today is to be in front of my computer, inside, so I’m trying to create an external relationship with outside. Now I’ve just inconvenienced the plant. Now I’ve put the environment in my service, rather than the other way around.

What I try to address are questions such as: How do I serve my community and my space so that the relationship is a reciprocal one? This pertains directly to the “isms” you’re talking about. Capitalism and commercialism tend to edify the extractive nature of the other “ism” you mentioned, imperialism. The doctrine of discovery, the ideology that everything is there to serve you, including people. The ideology that bigger is better, that building a 100-story building gives you power. Does that power become an identity? Does it give us a sense of belonging? It’s full circle, right? Most of us are looking for belonging, but we’ve become enamored by belongings. In the process of extraction, do we ever return what we take in full measure? Sustainability is balance. It’s taking and returning, giving and receiving. It’s not independence. It’s interdependence. I know we can’t go back, but I think we can go forward, perhaps by bringing forward practices from the past that were more in alignment with a sustainable way of life. It’s really shifting our mindsets from “carrying” capacity to “caring” capacity.

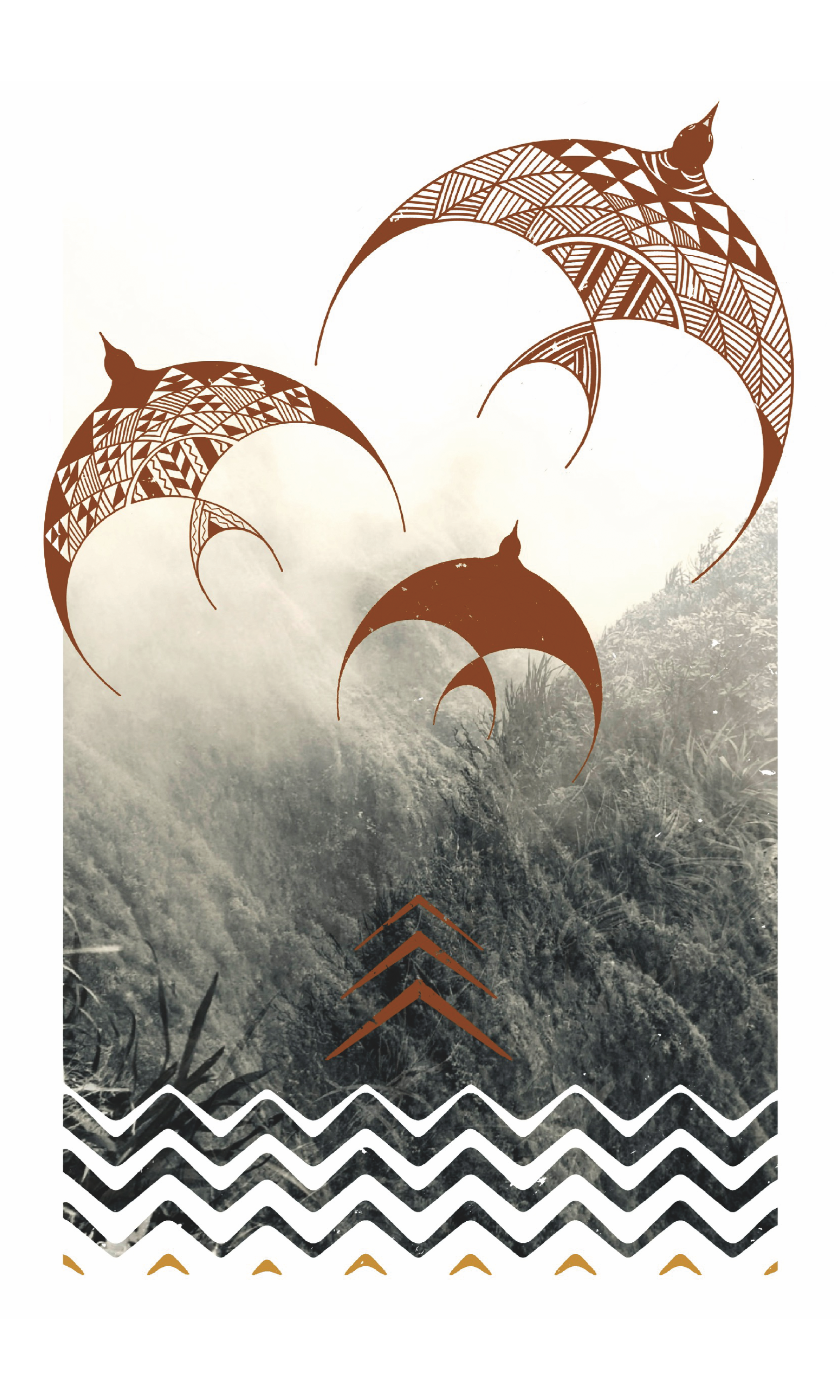

Kani Kīwa‘a ka manu i Waolani, 2022

This is loosely translated as, “the cry of Kīwa‘a, the mythical bird of the heavenly mountains.”

This and the previous illustration are inspired by the profound beauty of the Ko‘olau mountain range. Uncle Ramsay, and our Taum ‘Ohana, grew up beneath the shade of the tallest peak of the Ko‘olau mountains in Maunawili Valley.

IF

I love what you said about needing to look back to go forward. In design, there is often an emphasis on needing innovative solutions for our times. I think more and more we are realizing that some of the answers lie in history, in reacquainting ourselves with the past.

RT

A lot of my work is about that, but it’s not about going back anywhere specific. It’s about paying homage to what got us here. Let’s not forget that. Let’s not put our ancestors out of the house. They say, “the past is in the past,” but the past is actually the present. It’s right now. We’re living it. We’re living in the resultant conditions of what occurred before, whether it was yesterday or 50 years. Right now is an expression of what we did yesterday and the day before. But we must still ask ourselves, how do I want to live tomorrow?

IF

Thinking about it that way changes one’s perception of what a consequence is. The modern YOLO rhetoric of “living in/for the moment” sort of misinterprets what it means to be present. Of course, the philosophy of presence has been an integral concept to many intellectual and religious traditions, especially Eastern ones. But I think our contemporary sense of being present—which is sometimes to live without accountability, to make decisions without considering consequence—is not the true or intended meaning.

RT

Yes, and that’s the difference between caring capacity and carrying capacity. Sustainability has become about carrying capacity. But if you care enough, you’re going to choose behaviors that don’t require you to figure out how to carry, because it’s already done. Caring capacity versus carrying capacity is the same as accountability versus accounting; capitalism is an accounting procedure, not an accountability procedure.

IF

When we were working on the concepting for the issue, I was thinking that place is at the intersection of time and space. I think that’s kind of what we’re talking about, because it’s impossible to think about the meaning of place without considering time in the way that you’re describing, without letting go of some sense of its linearity or finiteness.

RT

I’d suggest that place is also time. It’s made from the time you spend somewhere and what you do with it. Of these little things I say—some of my students call them “Ramsay-isms”—I think the most important one, the one I’d like to leave you with, is the idea of shifting from reference to reverence. Let’s not just refer to things, but instead adopt a more spiritual and sacred relationship with them. That’s a big part of being in Hawai‘i because our relationship to place is sacred. It’s also the difference between being self-centered and being centered in self. What gives me the ability to be centered is knowing myself: learning how not to be a victim of externalities, but a creator of and respondent to what’s going on in me. Finding that internal compass within and creating places where I can go, when I need to retreat, reform, transform. At their best, the places we make hold the space for that.

Ramsay Taum is mentored and trained by respected kūpuna (elders) and a practitioner and instructor of several native Hawaiian practices: ho‘oponopono (stress release and mediation), lomi haha (body alignment), and kaihewalu lua (Hawaiian combat/battle art). Taum is a locally, nationally, and internationally recognized cultural resource, sought-after speaker, lecturer, trainer, and facilitator, especially when working with Hawai‘i’s industries, where he integrates native Hawaiian cultural values and principles into contemporary business. In 2009, he was recognized by the University of Hawai‘i as a Star of Oceania, an honor presented every three years to extraordinary individuals of Oceania for their work and service-related contributions to raising greater awareness around Oceania and its people to the nation, region, and world.