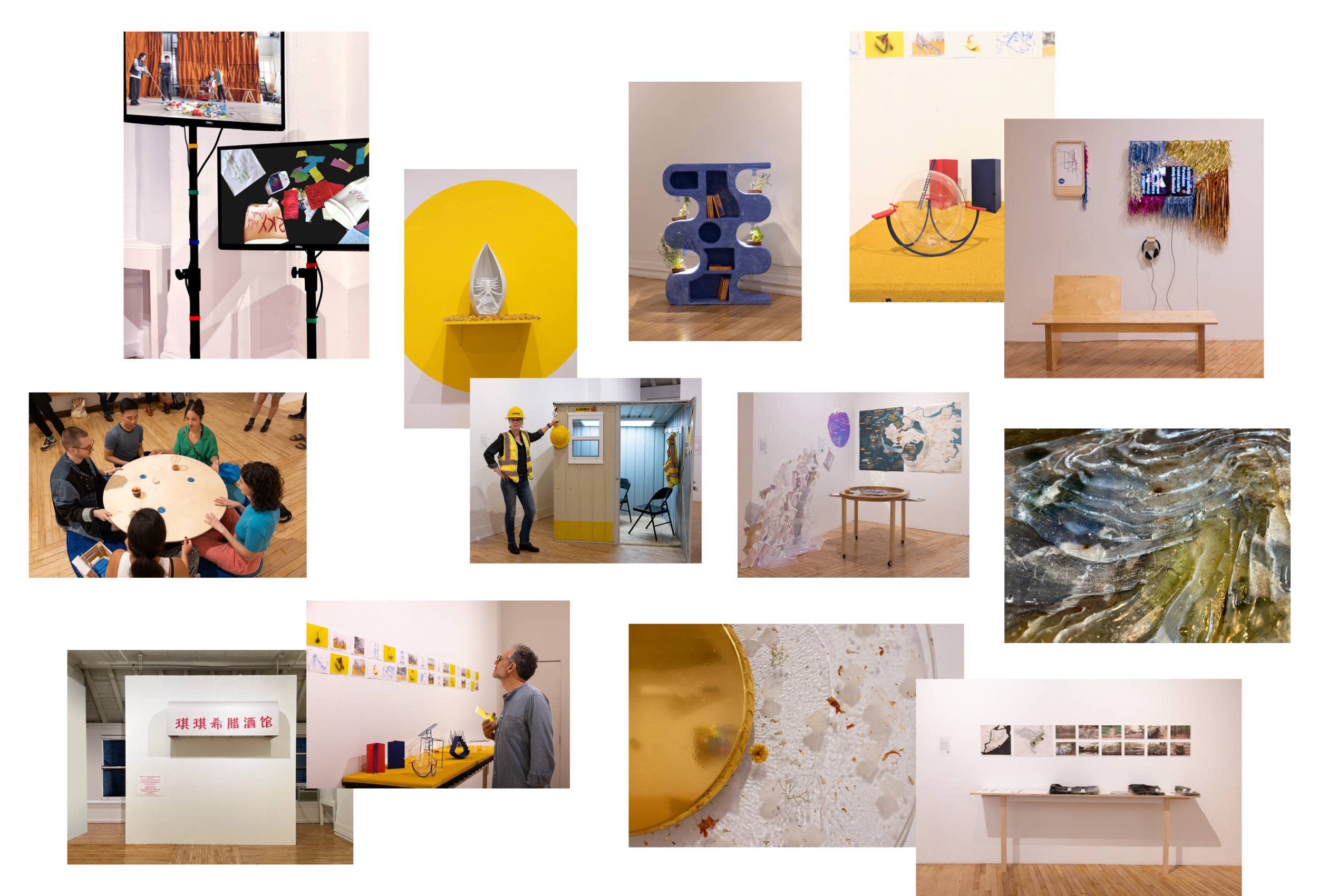

Emergent Emergency Strategies: 11 Takes On Collective Abundance

Over the course of the 2022-23 academic year, Deem editors Alice Grandoit-Šutka and Isabel Flower served as Mentors-in-Residence for the Collective Abundance cohort at NEW INC—the New Museum’s incubator for people working at the intersection of art, design, and technology.

This thematic track was imagined to creatively consider new models for wealth, health, and justice, through disciplines including architecture, hardware design, urbanism, art, and education. To culminate the experience, the cohort’s members staged the exhibition “Emergen-C Archive” at La MaMa Galleria in downtown Manhattan.

In their collectively-authored words for the show’s description, “the year shed light on the policies and philosophies that affect both the built environment and the psychologies of those who inhabit it, and their the exhibition was likewise rich in non-traditional approaches to archiving from and for marginalized perspectives, and forefronts the voices, memories, and potentialities of the disempowered. The infrastructures of mapping, zoning, land-use—and the urban social policies that comprise each—contain opaque mechanisms for recording and stratifying information that is rarely known to the public.

In contrast, Collective Abundance’s take on these subjects is iconoclastic and subversive: Lafayette Cruise utilizes afrofuturist imaginary to speculate life in a future Chicago; Eliza Evans questions the politics of property records; Amina Hassen and Muvaboard Studios confront representation and visibility in public policies; Melody Stein and Cara Michell problematize the erasure of social and ecological narratives inherent in Western cartography; MICROPOLITAN Studio reimages the psychogeography of the playground; Smita Sen activates memories of caregivers and loved ones through objects; Office Party considers the temporality and ephemera of nightlife. All of this is housed beneath Philip Poon’s playful reproduction of a Chinatown awning and Ana Ratner’s curving bookshelf, which holds a reimagined Old Farmer’s Almanac and a miniature library of living medicinal and local plants.

‘Emergen-C Archive’ illuminated elements of the past, present, and even future that we deem, collectively, to be important, and that are often excluded or expunged from traditional record-keeping. In this, we recognize the need for an emergent-emergency-strategy that, in keeping with the writings of adrienne maree brown, borrows from biomimicry in order to survive and embrace change with abundance.

To memorialize this moment of imaginative co-creation, we asked each of the aforementioned members to reflect on the time we shared in two parts: a. with a statement on how abundance shows up as a value system in their work b. with a description of the work they contributed to the show.

We hope that their sentiments provoke and expand on these important concepts for you, as they have for us.

01 Melody Stein

Melody Stein, On Willowed Ground; glycerin, beeswax, plaster, found materials, printed matter.a.

My approach to landscape design is shaped by valuing abundance. When I arrive at a site, the first question I ask is not, "What can I do here?" but rather, "What is abundant here?" Places already exist; the slate is never blank. Sometimes this abundance shows up as bountiful community input and engagement, a wealth of material resources, and a thriving existing ecosystem. Other times abundance can look like a profusion of invasive plants, a wealth of concrete, a surplus of urban heat. Challenges have affordances, too. Recognizing abundance is the first step in developing a design methodology that is neither the imposition of will nor an imitation of what the land would do, but, instead, is a response to it. The project I presented, On Willowed Ground, is an investigation of the abundance inherent in a place as a critical first step toward envisioning a potential future.

“Recognizing abundance is the first step in developing a design methodology that is neither the imposition of will nor an imitation of what the land would do, but, instead, is a response to it.”

b.

Reed’s Basket Willow Swamp Park is a public park in Staten Island. The site is a confluence of historical, ecological, and social forces shaped by willows, water, and the will of the people who have lived in, around, and in spite of it. A family farm planted in willows by an eccentric farmer in the 1800s, the land was acquired in the late 1970s by the state, and eventually assumed its current role as a site of public drainage, hemmed in by affluent suburbs. On Willlowed Ground is an investigation of layered, contradictory, and complicating narratives embedded in a landscape. It is about a place and the stories we tell about a place. It is a study in observational making, the first phase in a design proposal, and the seeded grounds for a new fable that blends mythology and the mundane in these muddy waters. As a landscape architect, artist, and writer, Stein blends practices of historical, site-based, and community-led research to design futures that emerge directly from past and present contexts and conditions. Special thanks to Flourish Lab for additional studio space and materials.

02 Office Party (Christina Moushoul and Chase Galis)

Office Party, Party: A Pedagogical Model; Two screens and two tripods. 32 minutes and 3 minutes.

a.

Parties are focal points of socialization or brief moments of high intensity that catalyze shifts in social structures. Over the course of a party, ideas, knowledge, and information are shared, increasing the collective knowledge base of its guests and severing or strengthening social ties. In our work, we argue that even after the party has ended, the networks it exists within—social, economic, material, etc.—continue to shift and change as the party’s effects reverberate through them across multiple time scales.

b.

In spring 2023, Office Party hosted a workshop exploring parties as a site for the generation of critical and counter-discourses in academic institutions. The price of admission was the completion of a reading selected from a predetermined bibliography that explores the role of collective gathering in relation to urgent concerns of architectural space-making, gender and sexual identity, and the politics of pedagogy. Party-goers and -crashers alike were encouraged to discuss their chosen texts as they simultaneously reflected on their embodied experience. Guests wrote notes on different elements of the decor and then discarded them on the floor of the party, accumulating ideas with the layers of garbage. Students were invited back the morning after to clean up the mess, as well as read and curate anonymous fragments of discussions that were left behind as an alternative archival practice.

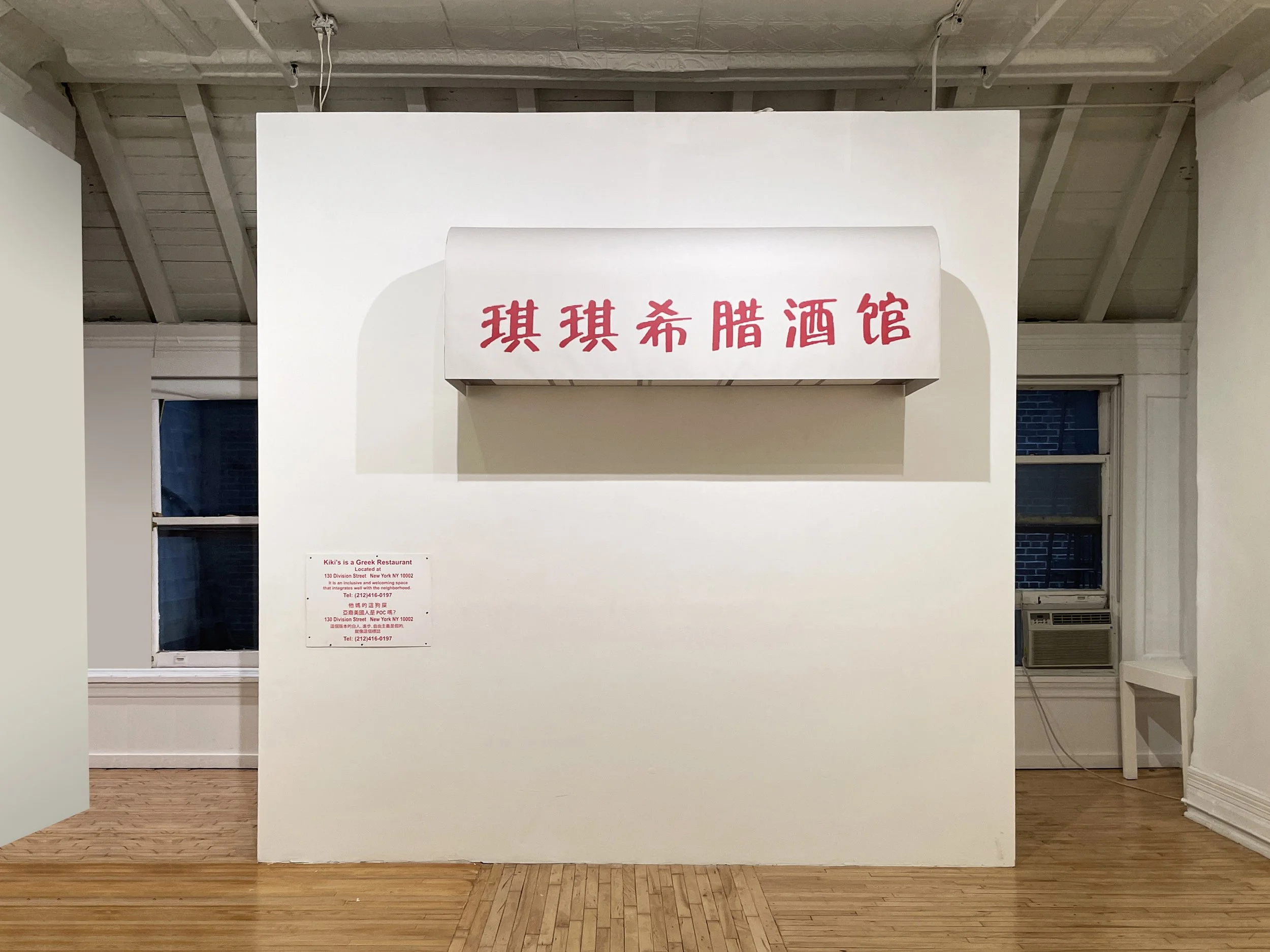

03 Philip Poon

Philip Poon, English Menu; Inkjet print, paper, board.

a.

It is sometimes difficult to adopt an abundance mindset when it feels like there are finite

resources, particularly in the context of New York City Chinatown. Is success contingent on the failure of others because physical space is limited? Is a new storefront the winner, and the one it replaced the loser? Does the winner have to rub it in the loser’s face? I can’t help but think about what older, immigrant, working-class Chinese people see and feel when they see new high-culture establishments in Chinatown. Do they even care? Are they too busy thinking about their rent? Is this a classist stereotype that I am projecting onto them? I’m a complicit culture-class Asian-American who speaks kindergarten-level Cantonese.

b.

Kiki’s is a cool Greek restaurant in Chinatown. This is its awning. The menu is in English.

04 Ana Ratner

Ana Ratner, Almanac Shelving Unit (a container for non-native medicinals); wood, paper-pulp, grow lights, catnip (Nepeta cataria), motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca), heal-all (Prunella vulgaris), st. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum).

a.

Every person looks through a different lens in order to make sense of the world. My brain often looks to plants and their interactions within ecosystems to help me understand how to be a human. A big conversation that's been happening in the foraging world is around plants deemed to be invasive. These plants were all introduced to the United States post-colonization; since they were not part of the ecosystem here already, they were able to spread rapidly and displaced many of the plants that had already been growing for millennia. Foraging has become hip recently (again? Or was it not hip when it was our ancestors' only option?) and with it an interest in harvesting rarer, native, edible, and medicinal plants. In this newish foraging boom, these plants are often overharvested for commercial use and, as non-native foragers, over-harvesting these plants for financial or social value is a continuation of colonization. For every single native ramp, wild ginger and "American" ginseng, there are 1000 introduced onion grasses, magnolia blossoms, and cleavers. These introduced plants are not boring, less tasty, or less medicinal than native plants—they are, simply, more abundant. If, as foragers, we can shift our idea of value away from endangered plants and onto abundant plants, we would be harvesting out what is prolific and making room for rarer plants to grow. My hope for my work is that it can help change how we think about value. So many people have deep knowledge and stories to share and I want The Other Almanac [a publication I founded] to amplify the abundant wisdom and research that doesn't always get a platform. Through plants, I've learned that if we can switch our understanding of worth to see value in abundance, instead of scarcity, we can begin to restore a more balanced ecosystem.

“Through plants, I’ve learned that if we can switch our understanding of worth to see value in abundance, instead of scarcity, we can begin to restore a more balanced ecosystem.”

b.

Almanac Shelving Unit (a container for introduced medicinals) is a bookshelf built to hold a new yearly almanac titled, The Other Almanac. The Other Almanac is a reimagining of The Old Farmer’s Almanac that bridges the urban and rural divide here in the US. It still has all the parts of a traditional almanac, but our pages are filled with art, recipes, historical critiques, and words from professors, climate organizers, Indigenous activists, farmworkers, scientists, medicine makers, incarcerated painters, astrologers, lawyers, borderland midwives, and more. The bookshelf, like the book itself, was created to bring agricultural, environmental, and rural knowledge into urban settings. This shelf is NYC-apartment-ready and outfitted with its own grow lights and planters. The herbs it contains are highly medicinal, prolific, and non-native, and grow wild all over New York State. Foraging for these plants in cities is not always recommended, though, like the almanac, these plants can also thrive in an urban home setting.

05 Smita Sen

Smita Sen, Expansions (sculpture) and The Manipura Sanctum (altar); 3-D printed resin, stainless steel bowls, paint, flowers. From the series, “Manipura: Of Flowers and Bones.”

a.

There is often an insistence in the American healthcare system that resources are finite. That access to care, insurance, financial support, medication, and healing is limited. That our health, like our lives, is finite. And that, as such, no one should have unlimited access to care. In the United States, healthcare is not a human right. This idea permeates the American healthcare system to the extent that the more disabled, sick, and elderly we are, the less we qualify for support. On the surface, it would seem plausible: that resources are finite and that full healing could never be possible. And yet, living as a full-time caregiver has shown me that there are still realms of abundance. In the systems of care that we create, both in and outside of the United States, there is an abundance of individuals willing to support one another through times of illness. There is an abundance of medical literature and an abundance of non-professionalized medical wisdom. The astronomical costs of care also suggest that there is an abundance of wealth in the American healthcare system, even as hospitals face resource shortages. As the world faces a global shortage of doctors and nurses, the ongoing impact of a pandemic, and a system in which advanced medical treatments are being hoarded by wealthy nations, conversations about the future of care are of the utmost importance. How can we create a healthcare system in which every single person within it—doctors, nurses, care-receivers, caregivers, pharmacists, and many others—is able to feel at ease? Is able to receive appropriate support? Is able to navigate illness with dignity?

The Manipura Sanctum art book and sculpture series has been an ongoing attempt to probe at these questions. Drawing from the theory and praxis of narrative medicine, each work is designed to bring the public together to reflect on their own experiences with medicine, caregiving, and community. Objects and spaces that are as much about gathering as they are about healing, the works of the Manipura Sanctum are an ongoing attempt to honor the needs of care-receivers and caregivers. They are an attempt to acknowledge the labor of caring for oneself and others through illness. A project that is constantly evolving, The Manipura Sanctum is a community space, a monument, and an honorific altar: an offering to the compassion and interdependence that healing illness requires.

In addition, this year and with seed funding from Recess and guidance from NEW INC mentors, I was able to gather a team to develop the Manipura Care Network, a nonprofit dedicated to supporting youth caregivers through the study and practice of the arts. With the support of NEW INC mentorship, the Manipura Care Network (MCN) was able to launch two programs: a workshop series for youth caregivers in partnership with the American Association of Caregiving Youth, and a summer fellowship program for a small cohort of young people who care for a sick, elderly, or disabled family member. As MCN develops, it is our sincere hope that we are able to continuously strengthen the support systems available to the youngest on the frontlines of care. Collective abundance, more than a lofty ideal, is a mentality and approach that can open new paths toward a future of care for all.

“How can we create a healthcare system in which every single person within it—doctors, nurses, care-receivers, caregivers, pharmacists, and many others—is able to feel at ease? Is able to receive appropriate support? Is able to navigate illness with dignity?”

b.

“In the last months of my father’s life, our family was absorbed in a whirlwind of hospitals, doctors’ visits, and at-home caregiving. My father had a complex and unusual illness that was not well understood by doctors. With the rapid changes in his health, we were forced to confront the limits of modern medicine and to untangle the complexities of the American healthcare system. I found myself asking a very fundamental question: What is healthcare? What does it mean to ‘care’ for the ‘health’ of someone else?”— from the introduction to Sen’s art book, Manipura: Of Flowers and Bones.

06 Lafayette Cruise

Lafayette Cruise, Musings from the Margins of a Polychrome Future; Baltic birch, mylar, tissue paper, digital monitor.

a.

Musings from the Margins of Polychrome Future is my container to expand our imaginations of potential futures and to ask questions that might reframe our approach to collective spaces, community composition, and urban planning. I’m concerned with the mundaneness of potential futures that center the pleasures and needs of those who are marginalized by the scarcity model of global racial capitalism. In the same way that the myth of a pure, white marbled antiquity has limited our understanding of ancient Roman and Greek society, our monochrome images of the future further limit our imagination of who is present and centered in it. The Polychrome Future asserts that there was an abundance of stories and perspectives in the past, present, and future; by centering those who are marginalized in the present we can imagine infinitely more futures where more folks are actively made to belong. The Polychrome Future is diverse, colorful, and dynamic—filled with the abundance of imagination and stories that we’ve artificially limited in our contemporary moment.

Lafayette Cruise, Musings from the Margins of a Polychrome Future; Baltic birch, mylar, tissue paper, digital monitor.

b.

The Musing from the Margins of a Polychrome Future installation at La MaMa Galleria was a future artifact. Viewers are asked to imagine themselves in a location that is dynamic and calming at once, like sitting on a bench in the park on a summer day or waiting for the train after a night out, or relaxing on a stoop on a late fall afternoon. The wall panel could be engaged in a number of ways: one could listen to the audio piece with or without the video, watch the video with or without the audio, or sit on the bench while the video and audio played silently behind. Viewers were encouraged to imagine those who will come after them, who will feel a sense of belonging because of the expansive world we’ve imagined; create a dream and a message to a future “you” from a present “us.”

07 Eliza Evans

Eliza Evans; Landman for the Planet; Landman office installation overseen by the artist herself.

a.

The animating principle behind my work, Landman for the Planet, is that people are willing to act against their (perceived) self-interests in order to create, contribute to, and support community. Community is not, in this case, confined to a geography, time, or demographic group. Rather, it's a community of value that materially demonstrates care for others who may be geographically and generationally distant.

b.

A landman negotiates oil and gas leases with mineral rights owners and landowners. In the US oil patch, the landman is notorious for possessing more charm than scruples. Currently, 17,000 certified landmen are working in the oil and gas industry, but none have previously focused on environmental concerns—until now. Seventy-five percent of onshore U.S. fossil fuel reserves are situated on private land, and approximately 12 million mineral rights owners receive $22 billion in royalties annually. Evans has become one of these mineral rights owners, unwittingly. Building upon the ideas explored in All the Way to Hell, a previous work where she distributed mineral rights to numerous volunteers to obstruct drillers, Evans introduces Landman for the Planet, which aims to leverage the landman's aesthetics, tools, skills, and craftiness to mobilize mineral rights owners to support climate initiatives. This multi-year endeavor will attempt to engage 1,000 New Yorkers with mineral rights in Texas. She will present these owners, who typically have economic incentives to support fracking, with options to invest in a just climate future instead.

08 Jamica El

Muvaboard Studios/Jamica El, Artifact from the Future (2035: 2035 U.S. Office of Advancement and Abundance); resin, gold leaf, flowers, Birch veneer plywood. Special thanks to Worthless Studios and the NEW INC community.

a.

So much of muvaboard's work centers ecosystems that have appeared throughout the universe. From constellations to ponds to parenthood, there is so much inherent placemaking and interdependence. What does it take for us to remember to be liberated in these ways? This question fuels the homages to and prioritization of nature, natural ways of knowing, futurism, and transparency in our studio work.

b.

Born out of President Maxine Waters’s new 2030 cabinet seat appointment, The Office of Collective Advancement and Abundance was created to ensure the global thriving of Black and Brown people. In this world of unprecedented climate migration, increased practices of cooperative economics, and artificially intelligent policing tools, strong pressure on government divestment in military research has bred a new federal office with a promise of ensuring everyone living under newly expanded definitions of “personhood” and “citizenship” are able to do so at the highest level of their desire.

Displayed are the office's original seal and materials from its first community program, Take What You Need (TWYN). The TWYN Program is globally renowned for the extreme simplification of assessment processes—removing bureaucracy, stigma, bullshit, and jargon from its materials and systems.

09 Cara Michell

Cara Michell, Participatory Map Table; wood, vinyl, paper. Fabrication by Free Tripp/Worthless Studios; Photo by Laurie Rhodes.

a.

As an urban planner and artist, I think often about how to distance my work from a model of individual ownership, and instead embrace the fruits of collective ownership. For me, that means sharing the process (and the credit) for creating new policies, stewarding physical spaces, and transforming the visual representations of our communities on a map. The cartographic conventions that I was trained to follow always felt limiting to me. During participatory planning workshops, I would try, futilely, to fit the complex social and environmental narratives that participants shared into a base map that was already governed by a rigid visual hierarchy and a scarcity of physical space. Each attempt to pick a geographic scale, a legend, and a boundary for the map became an exercise in excluding all or part of somebody's version of the place we were discussing. This is why I am so drawn to "alternative" mapping traditions (by alternative, I simply mean different from the dominant, eurocentric, projection systems that are used daily by the planners, architects, and environmental scientists who use Geographic Information Systems [GIS] to make maps). Psychogeography and other radical mapping styles allow us to step away from the scarcity mindset that "only the most critical information can be represented on this map." Because often that "critical" information is selected reflexively because it is in service to racial capitalism. Abundance in my work means including the Black Spatial Imaginary on maps, empowering teenagers to define their own research questions, and prioritizing underrepresented experiences and memories.

“Psychogeography and other radical mapping styles allow us to step away from the scarcity mindset that ‘only the most critical information can be represented on this map.’ Because often that ‘critical’ information is selected reflexively because it is in service to racial capitalism.”

b.

The participatory map table invites New Yorkers to collectively map locations of meaning around the city. This mobile workshop surface is part of Cara Michell's larger creative research practice, which asks how psychogeography can be employed to decolonize western cartography. Previous iterations of the map table have been on view at MoMA PS1 and Weeksville's 2022 Juneteenth Festival. Michell's forthcoming project, Black Psychogeographies, will explore culturally responsive approaches to representing African Diasporic stories through radical cartography. The map table represents a participant-centered approach to mapping, which rejects the cartographic frameworks that brought us the colonization of the Americas, the transatlantic slave trade, and red-lining. Using a somatic/psychogeographic approach, each map is co-created by three participants over a 30 to 90 minute workshop period. Some of these maps, each representing what the phrase "you are here" means to each participant, were on view at the “Emergen-C Archive” exhibition. Also on view was 826 Boston's Youth Literary Advisory Board Map, created in collaboration with Michell's research team and Boston-based high school students.

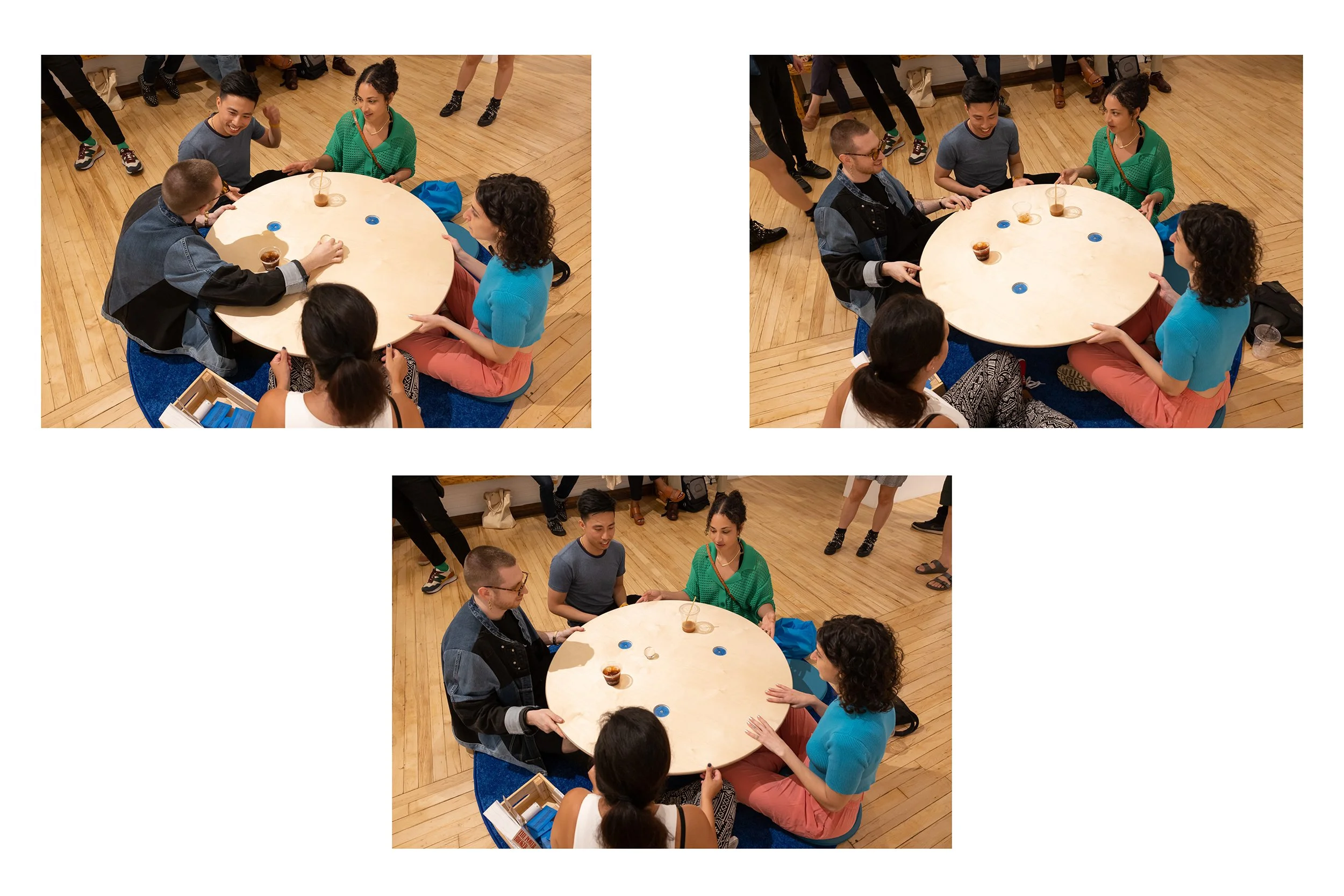

10 Amina Hassen

Amina Hassen, Tilted Roundtable; Birch veneer plywood, plastic, fabric. Photo by Laurie Rhodes.

a.

Abundance and generosity go hand in hand as values in my life and in my practice as an urban planner. Last year, friends gifted me with a Tarot card reading. Off camera, from a cabin in the woods in Canada, she told me that there is grace in both giving and receiving; be as generous with others as you are with yourself. I have been playing with finding that balance since. Throughout my time in the NEW INC Y9 cohort, I have been collaborating with a team of community-based organizations and technology providers on The Bronx is Breathing, a project that is building an electric charging hub for trucks in the South Bronx–New York State’s busiest trucking destination. We hope to catalyze a transition to cleaner delivery, making sure that South Bronx residents benefit first from the advances in clean trucks. Abundance and generosity are baked into the project in the way we’ve structured collective decision-making, power sharing, and cooperatives as the basis of viable business models.

b.

Tilted Roundtable intentionally has a rounded base, making it perpetually out of balance. Three inlaid bubble levels on the table's surface make a game out of leveling the playing field. Tilted Roundtable is a physical representation of a seemingly equitable invitation: a seat at the table, everyone sitting on equal footing. Like the group dynamics, politics, and urban development conversations that often play out over round tables, this table is perpetually out of balance, relying on a group, or an individual, to share either weight and responsibility in order for it to function.

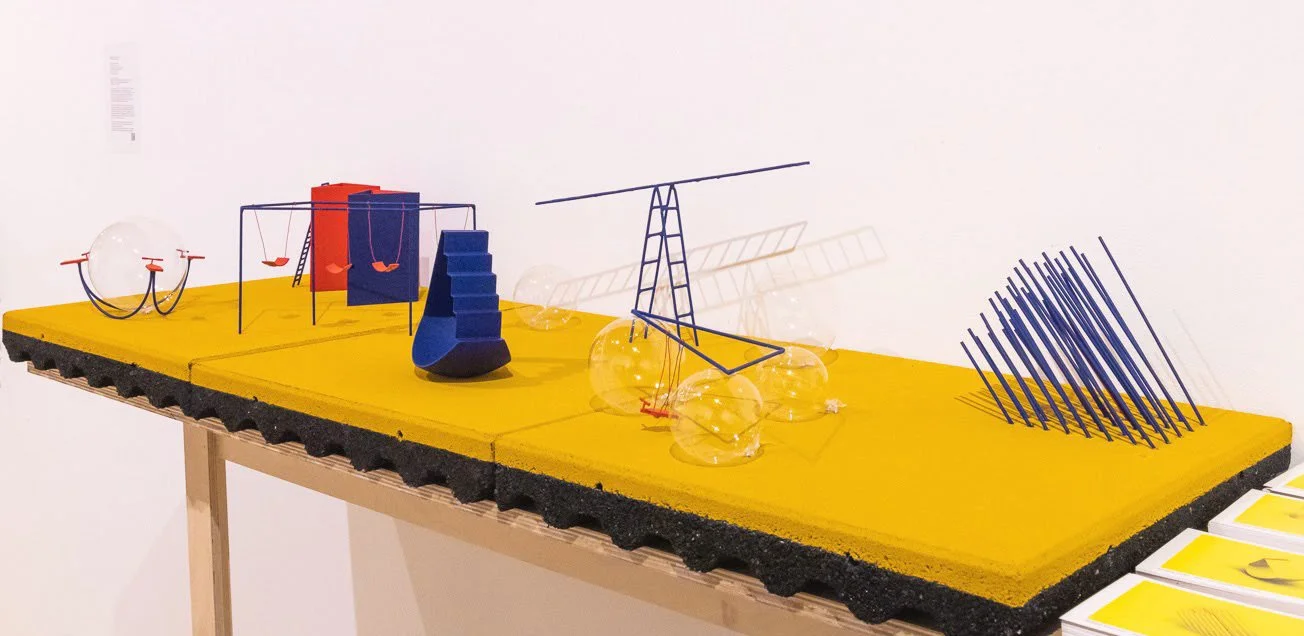

11 MICROPOLITAN Studio (Francisco “Pancho” Brown, Delara Rahim, Jimmy Pan)

MICROPOLITAN Studio, Playgrounds and Fear; rubber public parks playground pavers, printed art board, polyactic acid (PLA), inflatables, metal bar, paint. Photo by Laurie Rhodes.

a.

Our studio explores the concepts of “collective” and “abundance” through public space by using parks, plazas, and sidewalks as canvases and platforms to give visibility to what is invisible. Public spaces are inherently collective but increasingly contested, stripped down, or privatized. We believe that abundance is about redistributing public space for future decentralized forms of collectivity. In one of our first projects, Jardin de la Esperanza (Garden of Hope), we created a garden with a local women’s organization called Mujeres en Movimiento (Women in Movement) in Corona, Queens. Many of these women fled violence in Latin America, and we wanted to create a space of solace where they could plant, garden, dance, and liberate themselves from trauma inherent to immigrant stories from the region. For us, “collective abundance” is being able to create versions of this “public garden” for everyone.

b.

Playgrounds and Fear is a multi-phase project that explores the relationship between playgrounds and the unique memories they create. This work examines how this small public space can hold complex psychological narratives about the body and play. It counterpoints the contemporary playground’s focus on risk reduction, injury prevention, and safety. Through graphic and material experimentation, MICROPOLITAN studio playfully reimagines the psychogeographic effects of the core elements of the playground—the slide, swing, seesaw, and superstructure—to provoke memories of play and risk-taking. The suspended-in-motion miniatures are modeled by situations that allow the body to engage with risk as a core component of play.